In the category of reluctant

reader - surely the bane of every teacher and school librarian - boys usually

outnumber girls. How can you coax them into discovering there’s a whole wealth

of interesting, not to mention inspiring, information out there in the world of

books?

Introducing them to books about real people who came from backgrounds the majority of children can recognise may not complete the transformation from reluctant to eager reader [and more enthusiastic scholar?], but it could be a big step in the right direction.

The brilliant movie

‘Chariots of Fire’, which cleared the decks at the Oscars after its debut in

1981, brought Eric Liddell’s athletic achievements wide recognition. While, of

course, the movie focuses on Eric’s famous race at the 1924 Olympics in Paris,

it portrays both the athletic greatness and spiritual integrity of the Scottish

missionary.

‘The Flying Scotsman’ as

Eric Henry Liddell was affectionately known, was born in Tiensing, China, where

his parents, the Rev. James and Mrs. Liddell, were both missionaries. Eric

attended the local elementary school before being sent to join his brother Rob at

Eltham College in England. It was here Eric first showed his athletic prowess,

particularly his speed on the track. He was chosen to represent Scotland in both fields; unfortunately, though he was outstanding in each sport, his studies left him no time for both rugby and running. Forced to choose between them, Eric decided on running. His distances were the 220 yards and the 100 yards but he truly excelled at the latter.

Eric was an

automatic choice for the 1924 Paris Olympics;

his elation turned to dismay, however,

when he learned the 100 yards heats were to be held on a Sunday. In those days many

Scots observed Sunday as truly a day of rest. Sunday Dinner would be prepared

as far as possible the evening before! Active outstide games like football and

skipping rope were frowned upon. To run on Sunday was against Eric’s Christian

ethics. What could he do?

It was suggested

he run the 440 yards, a quarter of a mile. Eric hadn’t trained for this distance,

but he had a plan for success. Tension ran high. On the morning of the race,

one of the masseuses – from the American team I believe - slipped Eric a folded

paper on which he had written an encouraging message and which Eric recognised

as the masseuse’s variation on 1 Samuel 2:30: ‘He that honours me, him I will honour’.

Eric’s plan was to sprint the first two hundred yards of

the 440 to get as far ahead of the field as possible and then, he is quoted as

saying, he left it up to God to keep him fast. He won the gold medal in the 440

handily, and the bronze in the 220.

The following year Eric

returned to missionary work in China where Japanese aggression was making life increasingly

dangerous. In 1941, as the Japanese advanced, Eric sent his family to safety in

Canada while he remained to work at a poor station with his brother, who was a

doctor. They were overworked, lacking much of the medicine, equipment and food

they needed to help the desperate Chinese who came day after day seeking help.

In 1943, Eric was interned along with many others when the

Japanese invaded the station. Despite the privations, Eric kept up morale; he

taught Bible School, taught science to the children in the camp, and organised

games. Overworked, exhausted, and undernourished, Eric developed an inoperable

brain tumour. His earthly race finished, he died in February, 1945, just five months before the camp was liberated.

***

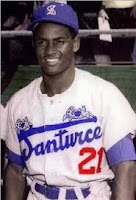

How many Puerto Rican

kids or kids of Puerto Rican descent have not heard of the great Roberto Enrique

Clemente Walker?

Roberto, born in Carolina, Puerto Rico, was the youngest of

seven children. When he was old enough he helped his father, a sugar crops

foreman, by loading and unloading trucks. Always interested in baseball, Roberto

joined Puerto Rico’s amateur league when he was sixteen years old and played

for the Ferdinand Juncos team. In 1952 he signed with the winter team,Cangrejeros de Santuce. This was a franchise of the Puerto Rican

Professional

Baseball League. While he was there the Brooklyn Dodgers offered Roberto a contract

with one of the team’s Triple A affiliates.

This meant a

move to the Montréal Royals farm team for Roberto but he never did play for the

Dodgers. When Pittsburgh Pirates scout Clyde Sukeforth saw Clemente, he told

the Royals’ manager that the Pirates were going to finish last in the league,

therefore had the pick of the rookies, and he was picking Roberto Clemente

Walker, no question.

His beginnings

in Pittsburgh were not the easiest for Roberto. The winter before his rookie

season with the Pirates a drunk driver slammed into his car at an intersection

in Puerto Rico and left him with a back injury which forced him to sit out many

games while he recovered. Because he was black, and spoke little English, the

sports media and some of the team gave him a hard time; announcers kept

referring to him as Bob, or Bobby, despite his preferring Roberto. His response to this was he had been raised never

to discriminate against anyone because of their ethnicity. As he proved his

worth, Pittsburgh loved Roberto; his number was changed from 13 to 20, the

number of letters in his full name.

In 1958 he signed for the U.S. Marine Corps. Under their rigorous training he gained ten pounds and had no back problems. By then Roberto was so invaluable to the Pirates team that State Senator John M. Walker sent a letter to U.S. Senator Hugh Scott requesting his early release from the Marines in 1959. Roberto remained a Marine Reserve until September, 1964.

His rewards in baseball were many,

culminating when he earned the World Series Most Valuable Player trophy, yet

far outflanking those are his rewards in how he has lived, in what he has done

to help others. He helped financially, never to gain recognition but simply

because he could, and wanted to. He cared about children especially; his dream

was to build a ‘Sports City’ where young Puerto Ricans would have access to

coaching in many sports, facilities, and encouragement. In the off-season he taught

baseball and ran free clinics for kids in Puerto Rico, especially those from

poorer families. He loved his country and did much to raise the status of

Puerto Rico and Latin America in the world’s eyes. He was involved in a great

deal of charity work, and when Managua, the capital of Nicaragua, was hit by a

massive earthquake on 23rd December, 1972 he immediately began

arranging relief flights. When he heard the aid on the first three flights had

been siphoned off by the corrupt officials and never reached the victims he

decided to go on the fourth flight himself, in hopes his presence would shame

them into honesty. On December 31st he set off on an overloaded plane

with an incompetent crew. It crashed into the Atlantic Ocean immediately after

takeoff due to engine failure. Roberto’s body has never been recovered, but his

legacy lives on in the selfless work he did during his lifetime.

***

And now we come to the

last of our sports heroes, who was in his own words a really rotten kid, Louis

Zamperini. With co-author David Rensin, in his book ‘Don’t Give Up, Don’t Give

In’ he speaks for those kids who are seen to be seriously off the tracks.

Born in America of Italian parents who spoke Italian at home, he went to kindergarten in California speaking very little English, and very poorly at that. He hated recess when the other kids would surround him to taunt and jeer, to punch and kick him over his poor English, his wiry

hair, and big

ears. Eventually his father made him a punch bag, so that Louis learned to

fight back – and win.

His older

brother Pete was the model son who could do no wrong, and Louis the changeling

child who could do no right. He felt he could never live up to Pete, so Louis

set out to be as bad as he possibly could be. He was forever getting into

trouble with the police, with school, and with his parents. One would think

Pete might get fed up with Louis but he never did. He loved his little brother

and when all three of the authorities mentioned above were at their wits end,

Pete took Louis to the local steel mill, where the workers ‘looked hot, greasy,

and dirty’. Louis was aghast. He didn’t want to end up like that, and Pete

pointed out that’s exactly where he would end up, unless he smartened up. He

warned Louis that no one could force him to turn his life around – he had to

want to do that himself.

The school

officials decided to give Louis another chance, especially after Pete suggested

sports. Too small for football, Louis was entered in an interclass race to run

the 660 yards with the promise if he ran, his school slate would be wiped

clean. He ran. He came in last, in pain and suffering from having smoked since

he was six years old. But the running bug had caught him. He ran, and in

running and eventually winning, he found self-respect. He set himself to learn

at school, recognizing the importance of education.

Adrift on a

raft in the Pacific Ocean for many days before being captured by the Japanese

in WWll, Louis endured the brutality of their prison camps. Beaten day after

day, he stubbornly refused to give in. When he was finally liberated and

returned to America, at first it was great and then it appeared Louis was once

again on the slippery slopes. Until his wife persuaded him to hear Billy

Graham. Louis finally realised hatred consumes and destroys the person who

hates, and accepted Christ in his life. He worked tirelessly to help young people

improve their lives, applying Christ’s teaching of love and tolerance, tough

yet encouraging.

***

All pictures

are, to the best I can ascertain, in the public domain. And to those who query

why my name isn’t on the authors list, it’s because Chris started this blog,

and I don’t want to mess it up.